You Write the Way You Love: Interview with M. Evan Wolkenstein

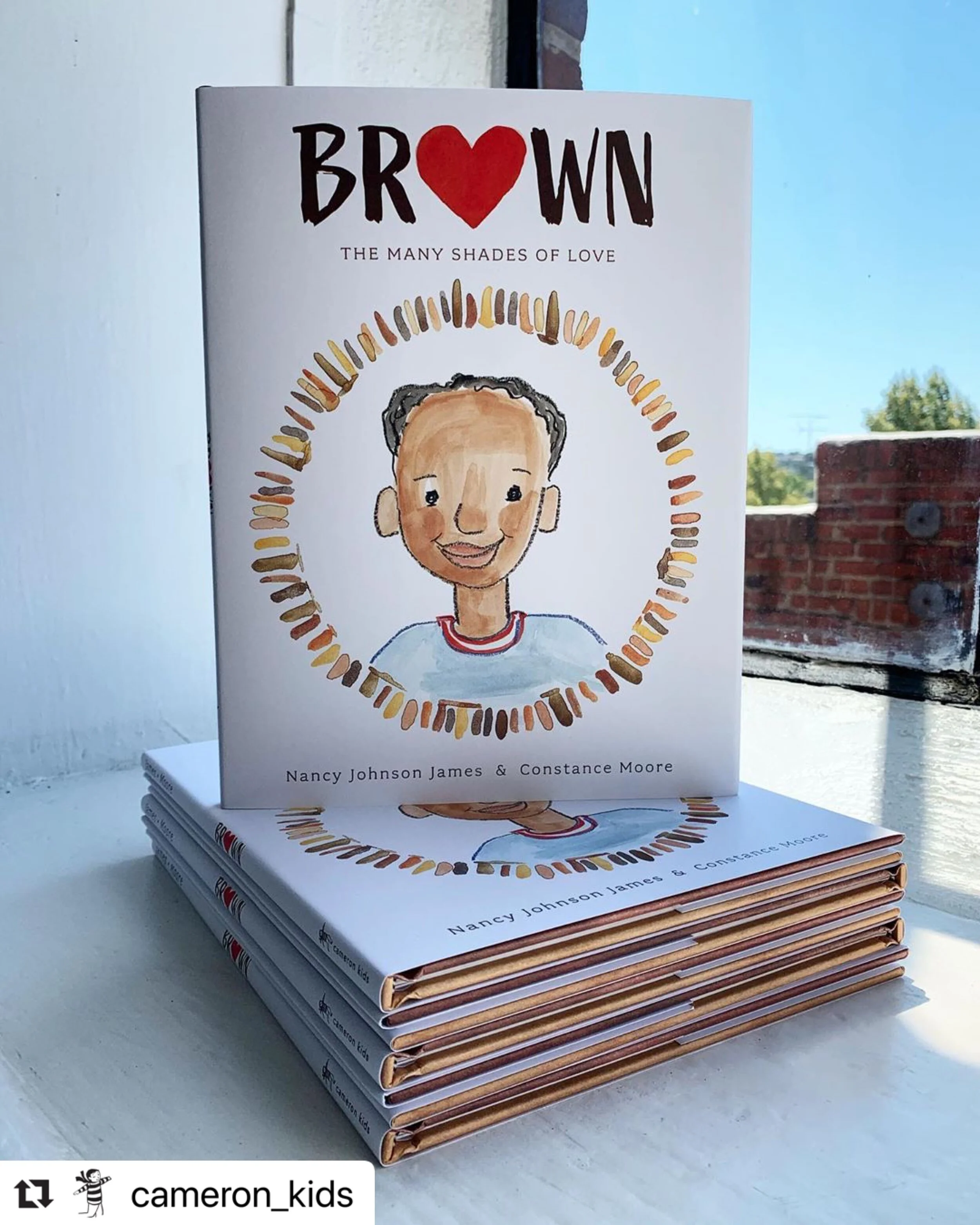

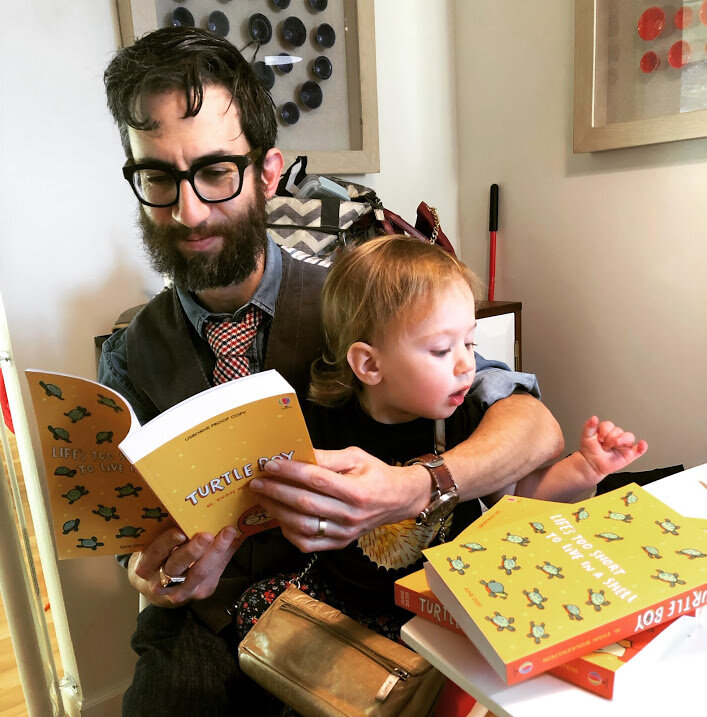

M. Evan Wolkenstein’s YA novel, Turtle Boy, comes out tomorrow. Published by Random House on the heels of an already-diverse essay writing career, Turtle Boy is about learning that life is too short to live in a shell.

“Writing is a lot like other things in my life that I love: my wife, my daughter, Judaism, teaching. There isn’t one thing I love about any of them, but rather, it’s a bucket of things—a big, giant bucket. I cycle through everything in it, some routinely, following the calendar, and some things pop out on their own—SURPRISE!”

A high school teacher living with his wife, Gabi, and daughter, Anna, in the San Francisco Bay Area, Evan attended the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Hebrew University, and the Pardes Institute for Jewish Studies. In our interview, this Sexy Grammar writer reveals how he translated his experiences being bullied as a youth into style and his style into storytelling.

What are your three favorite images from the book? No spoilers!

I wrote this book to be very visual, very cinematic, to appeal to young readers, but also because I’m a very visual person and I experience the world powerfully in colors and textures and shapes.

Scene 1: Will has gone to his secret hiding spot, a nature preserve. He is surprised to discover that his loud and hyperactive friend, Max, has located the spot on his own. Max has beaten him there, and he has climbed aboard a parked, inactive excavator. Max is really into parkour, and he has climbed up to the machine’s arm. He’s balancing on it, jumping and leaping and showing off his balance. That balance comes in very useful later in the story, but right now, Will comes upon Max and, because he is afraid of heights, he is shouting for his friend to come down. But Max is having the time of his life.

Scene 2: Will is extremely shy, but through a series of events I won’t reveal, he finds himself doing a performance: he’s alone on a stage, wearing a mask, and pouring his heart and soul into what he’s doing. The lights are glaring in his eyes, and suddenly, something goes wrong and he needs to make a really big decision. While I was reading this scene in the recording booth, I actually started getting vicarious stage fright. My heart was pounding and my voice got dry, and I think it might even color my voice in the recording.

Scene 3: Towards the end of the book, Will is involved in a prayer service where one of the most common Hebrew prayers, the Kaddish, is being recited. He can’t say it aloud, so he adapts it by blending the traditional Aramaic (fun fact: the Kaddish is not in Hebrew) with his own twist. I’m really proud of this moment—definitely an instance of the text writing itself. And now, when I say the prayer in synagogue, Will's voice comes to me.

Tell me a story.

Here’s one of my origin stories.

In sixth grade, kids started saying that I looked like a turtle. I didn't know what that meant. Did I have a shell? Eventually, I figured out that they meant that I looked like "Cecil the Turtle" from Looney Tunes. Slowly and inexplicably, my chin had receded. My parents brought me and my strange chin to a doctor for X-Rays. The diagnoses: some sort of maxillofacial condition along with arthritic erosion of my jaw-hinge. No corrective surgery would be possible, the doctor said, until I was in my mid-teens. That span of time was equivalent to a third of my life. He might as well have said: "This hell will last until the sun goes supernova."

Starting high school as a freshman meant a new crop of bigger kids to tell me what I looked like. I spent most of my days hiding from bullies and most of my afternoons drawing superhero comics. Then, something new! Debilitating nausea! The doctors ran tests. Everything came back negative. I was referred to a therapist who made me stand in front of a mirror and describe myself. I talked about my hands. I avoided my face.

The next summer I actually had the surgery. Recovering, teeth banded together, I drank liquified hamburger and learned to swallow spaghetti without chewing. I took guitar lessons. When I returned to school, amazing, no one said a thing. No: "Nice chin." No: "Whoa! What happened to YOU?" I wasn't sure what to make of this. Did the surgery fail? Were people being polite?

I grew my hair out and poached a pair of "granny glasses" from my parents' antique collection. I hid behind this costume for the next five years, augmenting it in my mid-twenties with an unfortunate goatee.

When I turned 30, I needed new glasses. I'd brought a friend with me and she pushed me to buy the edgiest, hippest frames they had. I got compliments from cashiers, bartenders, and baristas. I got swept up in the transformation. I surrendered my decade-old look and began to explore style in earnest. I tried new things, ready to stand out. I took a daily selfie to document my successes as well as the occasional disaster. Because I was focusing on my clothes, I became more and more comfortable with looking at myself. My face was no longer a problem.

I met Gabi, my future wife, and she encouraged me to write about what I'd been learning about style and self-acceptance. I started a blog called Style For Dorks. That led to my novel,Turtle Boy, about my fictional 7th-grade alter ego and his journey towards self-acceptance.

There are two of me: a confident teacher/writer/husband/father, and a 13-year-old turtle. There's no way to make the turtle go away, so instead, I try to be compassionate. I try to be understanding. I send him a picture across time and I say: one day, this is how your life will look.

Describe your writing process in as much detail as you dare.

In high school and college, I was very precious about my writing. I would go to a cafe and wait for the perfect table with a commanding view and sip my black coffee in titrated doses with the exact right Jazz playing on my walkman. I would write 19 sentences of florid prose and exhausted, quit for the day. That’s probably why I wrote two (incredibly over-written) short stories a year and then dropped out of the game. Too much pressure. Too much perfection. Too much self-indulgence.

Now, as a full-time teacher and father of a two-year-old, I can’t afford to be precious about my craft. I get up at 4:45 am, make some tea, and write for 75 minutes. After Anna goes to bed, 90 minutes. I get some garbage on the page and clean it up later.

What do you love about writing?

Sitting down daily to write is a lovely routine. So is bed/bath time, Shabbat candles, talking with Gabi before going to sleep. That’s all about repetition and the combined power of a simple thing over time.

But then there are moments when I’m swept up in the joy: knocking out a fan-fucking-tastic scene, a piece of prose emerges from who knows where. Anna will do or say something that blows me away—saying the Shema when we’re walking in the park. Or Gabi will tell me the exact magic thing I needed to hear in a given moment. Or a Yom Kippur melody will bring me to tears.

Sometimes it’s about giving, and sometimes it’s about getting: knowing my story might open people’s eyes, might bring light to their world, is incredible. But so is the feeling of being in my own flow. There’s guiding Anna in her young life and the way she makes me laugh. There’s my personal feeling of community, and there’s the way I try to give to my students, everything that I’ve got. I guess you write the way you are. You write the way you love. You teach who you are. You love in the same way that you teach. And you practice your identity in all these very same ways.

###

I coax sexy writers like M. Evan Wolkenstein to reveal their creative secrets and processes in writer interviews to inspire you:

Read Turtle Boy and more of Evan’s work on his website.

Follow Evan’s story, including his selfie-a-day project on Instagram and the Style for Dorks blog.

Follow Evan on Twitter, and read his essays in Forward, Washington Post, Engadget, and BimBam.

Feeling inspired? Book a private session with me, The Sexy Grammarian. You always leave private sessions with homework and inspiration, and the first session is always free.